TODAY’S tale starts at the end, not the beginning.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

It was a sombre day in January 1908 when the famous Stockton Colliery finally stopped hewing coal after 23 years.

For years it was one of the biggest employers in inner Newcastle. Its miners worked in harbour tunnels of the Hunter River estuary, a short-lived practice known as delta mining.

Briefly at its peak, Stockton Colliery employed 439 people, mostly miners.

Soon it would be no more. Buildings were quickly dismantled and pumps removed, finally leaving just a few surface scars near the Stockton waterfront as a reminder. During this underground pit’s lifetime it had probably produced almost 3.5million tons of coal.

The Stockton mine won its first coal in March 1885 after sinking a shaft to a depth of 367feet (111metres) through sand, quicksand and solid rock.

But it was worth it to secure the future of the colliery, its mine staff and their families. The miners struck the rich Borehole Seam deep below which was described as being “29feet [about 8.4metres] thick”.

But now, in 1908, the mine was no more. Proof of the melancholy task of mine closure came with the pit tunnels swiftly filling with water, rising in the shaft to almost 18feet (5.4metres) of the surface.

These days, there might seem little to remind people the big colliery ever existed, except a few street names and historic plaques.

In local memory, however, the Stockton Colliery name vividly lives on, mainly because of a major colliery disaster in 1896.

It still remains one of the worse tragedies of the Newcastle coalfields, although similar disasters at Dudley (in 1898) and Bellbird (in 1923) claimed more lives.

In the December 1896 Stockton Colliery accident, there were 11 victims. What increased the horror was that after six workers were initially overcome by noxious gases deep below the earth, another five brave men then died trying to rescue them.

Coalmining has been part of the Hunter Valley for more than 200 years, since the days of the first convict miners. Thousands of people still work directly in mining.

A timely reminder to all of how dangerous coalmining is has come with the two recent tragic deaths at the Austar underground mine at Paxton, south of Cessnock.

Their names will be added to the memorial wall at Aberdare which contains a staggering 1800 names of miners killed in the Hunter Valley. And this is despite the reputation of Australian mines being among the safest in the world.

Mining has always been hazardous, though, and Newcastle’s rapid growth in the fuel-hungry 19th century depended on coalmining. In 1897, the year after the Stockton disaster, 58 pits were operating in the Newcastle district.

Attempts to exploit the Borehole Seam coal beneath Stockton started as early as mid 1869, but excessive water and quicksand halted this. The 1885 shaft sinking was more successful, creating great work prospects.

The 1896 disaster, however, made the colliery a household name for the wrong reasons. It started about 4am on December 2, 1896, when the bodies of two men, George Curran and Charles Smith, were found below at the ventilation furnace. They had died probably four hours before, overcome by a thick, deadly mine gas, possibly carbon monoxide produced by a fire in some abandoned workings.

Despite the gas risk, the bodies were recovered by mine deputies. All coalmining ceased.

The next night, after the two funerals, an exploring party of 12 men ventured underground to check on the probable fire source. Their 9.30pm departure was to allow any accumulated mine gases to disperse, after directing more air currents deep below. But poisonous gas pockets soon meant members of the investigating party starting to fall over, or start running. More rescuers arrived to help, but four members of the exploring party were fatally overcome by mine gas. Six men were now gas victims.

Another rescue attempt was then made, this time led by mine deputy Robert Jury. Some of the group, after losing their direction, were also overcome by carbon monoxide fumes.

Five men had died courageously trying to save an earlier gassed mining mate, Thomas McAlpine.

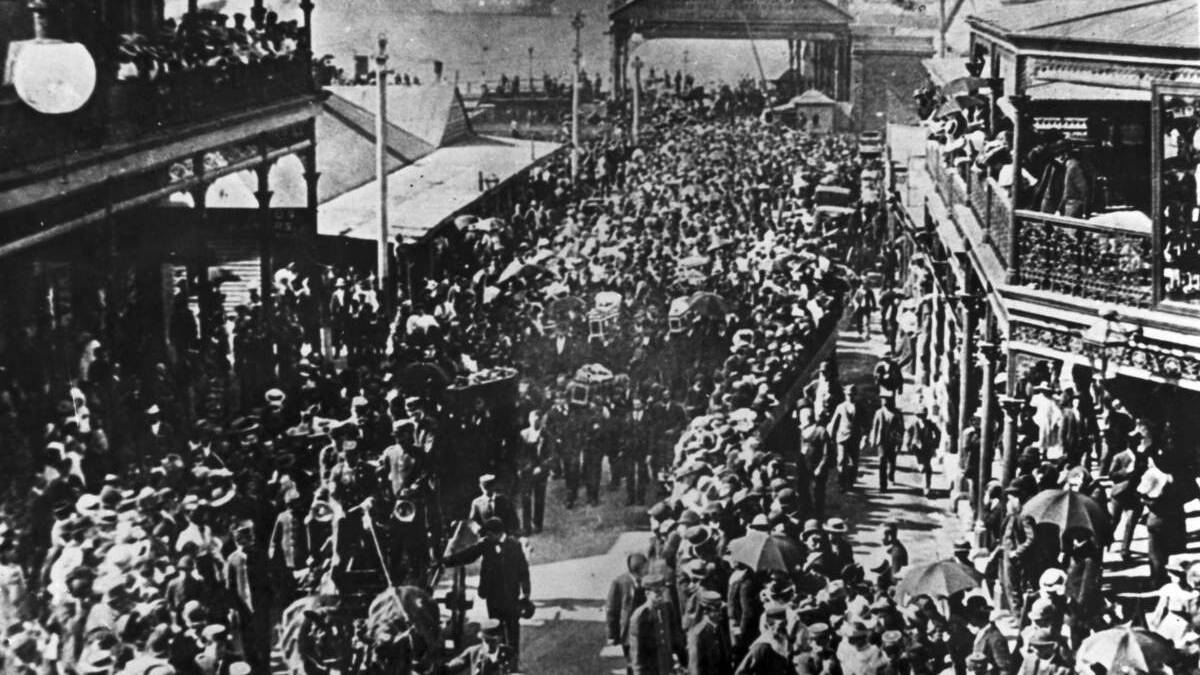

One young rescuer who survived was Robert Drylie. He braved toxic gases in the old workings six times trying to help others. All bodies were recovered, the old dangerous workings bricked off and on December 5, the public funeral of eight of the 11 victims was witnessed by thousands. The eight coffins were brought across on one ferry from Stockton to Newcastle while four other ferries carried the mourners.

Rare historic pictures from the occasion show the coffins being borne shoulder high through the then Market Street railway gates en route to the funeral train to Sandgate Cemetery.

The names of all the mine victims were later commemorated on memorial pillars erected by public donation at Stockton’s Lynn Oval in August 1897.

The centenary of the pit tragedy in 1996 was then marked by the planting of an avenue of 11 trees in Stockton.

Hunter coal historian Ed Tonks, of Charlestown, learned much of the pit’s machinery and many staff transferred to a new Borehole Colliery at Teralba in 1908. The Lake Macquarie mine soon became known as the Stockton Borehole Colliery.

Another historian, the late Dr John Turner, always maintained Stockton Colliery was one of the sad stories of Hunter coalmining.

In 1885 it was producing good quality gas coal, but the Stockton mine owners deserted a coal demand share pact (or Vend system) and supplied coal to the Melbourne Metropolitan Gas Co for six years.

When this contract expired, the gas company cut its price and “for years after that the Stockton mine could make little profit”. A serious depression in the 1890s had forced coal prices and wages down to their lowest point.

Miners were prepared to work for half pay to simply keep their jobs. A total of 28 lives were lost during the operation of Stockton Colliery up to 1908.