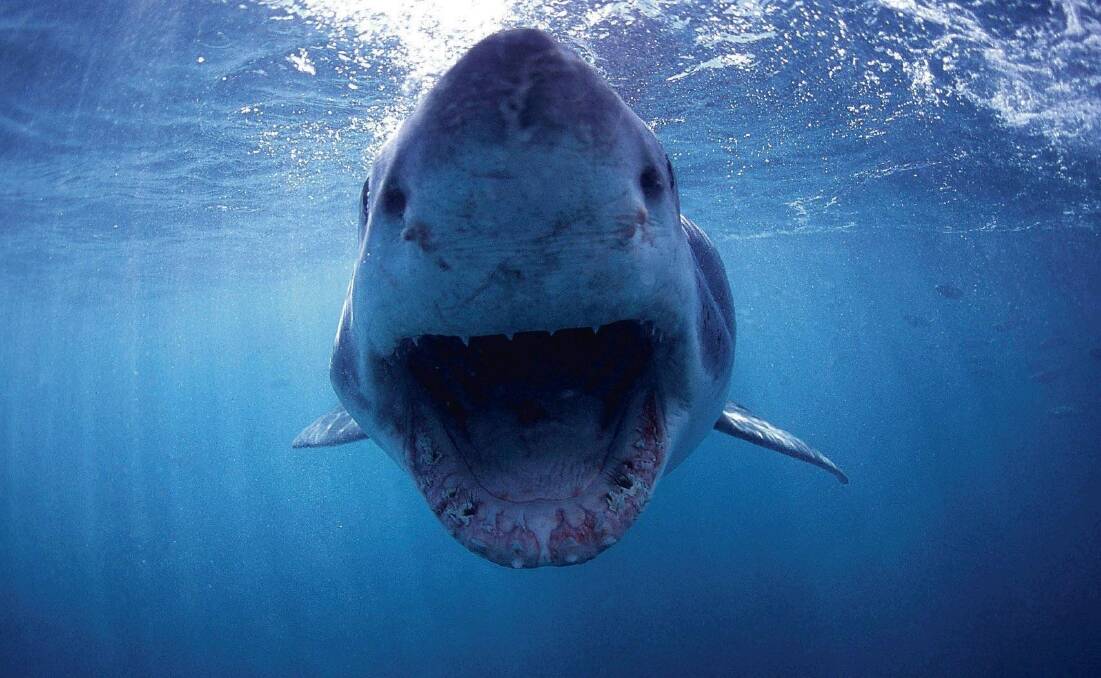

AFTER two shark attacks in 10 days off Ballina’s beaches, Premier Mike Baird announced a six-month trial of meshing this suddenly very dangerous piece of coastline.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

The announcement came on top of other measures, “smart” drumlines, tagging, and sonar buoys, in a further attempt to reduce a dramatic increase in attacks on local surfers and swimmers.

It inspired relief among many of Ballina’s surfers and businesspeople, who’ve been dreading the news of another fatal attack and its potential effect on the town — yet it also raised angst among green-thinking people, who dislike the idea of sharks and other sea life dying in human-laid traps.

Indeed, the whole idea of “shark nets” seems to press some serious buttons for everyone.

But beyond the relief and the angst: what IS meshing? What does it do? What are its effects on marine life, and on human encounters with big sharks?

Trying to answer these seemingly simple questions, I obtained a range of documents that give a full picture of shark meshing programs in both Australian and foreign waters over the past 80 years, since meshing was first introduced off Sydney’s beaches in 1937. I also talked with Liz Volep, author of an honours thesis on bycatch in the southern Queensland shark control program, which has been in existence since the 1950s.

Shark net meshing was thought up by the NSW Fisheries in 1936, after a decade and a half of relentless attacks off Sydney beaches. You think Ballina was bad; at times it must have seemed like swimming in Sydney was suicide. In March 1935, for example, two people — one at North Narrabeen and one at Maroubra — were killed by great white sharks in a single week.

The meshing was never designed to enclose a piece of water — even back then, they knew barrier nets would never survive a surf zone. Instead, it was designed to catch large dangerous sharks as they swam within range of the surf. At first, the catch was huge; over 600 sharks in the first year of operation, off just a few Sydney beaches. But over time, even without adjusting for the spread of the program across almost all Sydney beaches and into Wollongong and Newcastle, the catch declined. (Liz described it to us as “almost an exponential curve”.) Today’s NSW meshing annual average catch is 143 sharks, quite a number of which are released alive.

Both NSW and Queensland’s programs are a lot more sophisticated than they used to be. Queensland’s program is bigger and more expensive: 83 beaches are meshed compared with NSW’s current 51, and Queensland also employs numerous drumlines, from the Snapper Rocks area all the way up to Cairns. As a result, Queensland’s shark catch is way bigger — in 2015 alone, for instance, it captured 297 tiger sharks, mostly in northern waters, and mostly on drumlines, which are considered more effective in catching large sharks than meshing. (Meshing is pretty effective against bull sharks in turbid water, which might help a bit at Lighthouse.)

Liz told us that meshing is thought to work not just by reducing a local shark population, but by interrupting their behaviour: “Sharks are territorial animals, and if something is there to prevent them setting up a territory, they won’t like it.” But this is just a theory, not flatly proven beyond doubt.

What does seem obvious is when it comes to separating humans and large sharks, meshing works. In the years from 1900 to 1937, 13 people were killed off NSW surf beaches by sharks; over the next 72 years, the death rate fell to eight, only one of which was at a meshed beach. This in a period when the NSW human population rose from 1.4 million to seven million — and when way more people began going to the beach.

Similar figures can be seen elsewhere. In Dunedin, New Zealand, between 1964 and 1968, three fatal great white shark attacks occurred off a series of local beaches. Local authorities took a look at the NSW meshing program, and nets were laid off those beaches; nobody has since been attacked in the area while the nets were set.

Correlation is not causation, it is said. But ask yourself, if you’re a Sydney surfer — do you feel safe? What about if you’re from Ballina?

Then there is the emotionally loaded, and occasionally very visible, issue of bycatch. It’s one reason why the authorities have been so cautious about meshing Ballina’s beaches — the idea that the nets kill a lot more than just sharks.

The records make it clear they do — but perhaps not nearly as much as you’d suspect. Meshing is supported by pingers designed to alert marine mammals to their existence, and by and large they seem to work. In NSW, the meshing averages one humpback whale every two years; the whale is almost always released alive. In Queensland in 2015, the bycatch included one bottlenose and seven common dolphin (one released alive), 11 catfish, eight cow-nose rays, nine eagle rays, 13 loggerhead turtles, five manta rays (all but one survived), eight shovelnose rays, three toadfish, four tuna, and a white spotted eagle, which was safely released.

In the same period, four people were attacked by sharks in Queensland waters. One was injured, the rest weren’t. Nobody died.

Oh, and here’s something else the records make clear. If you’re worried about sharks’ survival, or sea-life bycatch in general, you’re way better off looking offshore. Australia’s commercial shark fishing industry is taking over 1200 tonne of shark out of our various fisheries each year: everything from gummy shark to mako, and very likely a few white sharks as well. The NSW prawn trawling industry alone results in 64 tonne of shark as bycatch each year. Six percent of what’s caught in the tuna longline fisheries in northern Australia is shark.

And guess what, hardly anybody is able to find out what else is being caught up in the melee, because most of the reporting is left up to the fishing crews themselves.

Next to that action, as the figures show, surf zone protective meshing is a minnow in a very big pond.