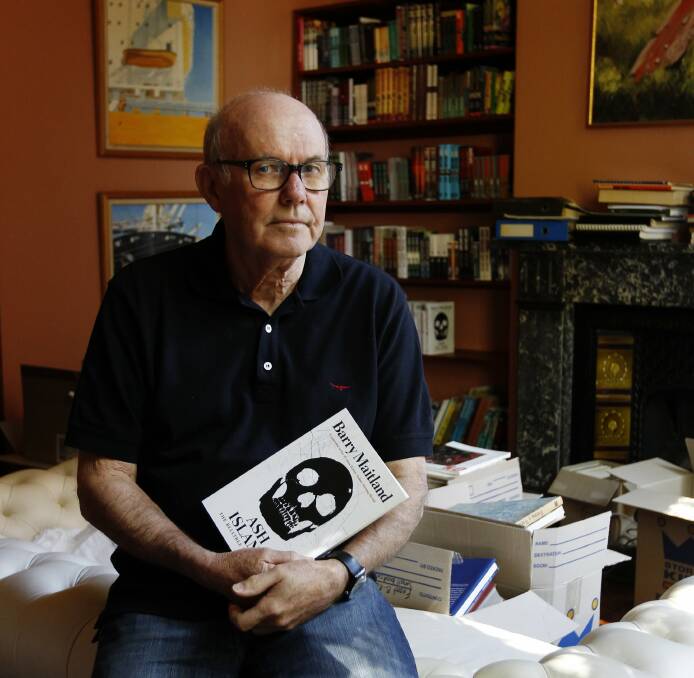

WITH words as a weapon, Barry Maitland has his characters commit dramatic crimes in his novels. Yet by the look he gives, it’s me committing a crime with words when I ask Maitland if he is a Renaissance man.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

“No,” Maitland groans and rolls his eyes. “No, it’s embarrassing. Because everybody surely does lots of different things.”

Well, yes, but not everybody has been a respected architect and academic, painter and best-selling crime novelist. Especially not at the same time.

I meet Barry Maitland at Seraphine Cafe in the city’s art gallery, which hosted an exhibition of his expressionist landscape paintings, The Forest Floor, in 2016. So I’m lunching with Maitland in Maitland. Even though he has lived in the Hunter River city for more than a quarter of a century, the man still hears jokes about the surname he shares with the place he calls home.

“People tease me about it,” Maitland says, sipping white wine. “Ordering takeaway on the phone - ‘Yes, but what’s your name?’.”

Crime fiction readers know his name. Maitland has written twelve books in the Brock and Kolla crime mystery series, as well as a thriller, Bright Air, and the Belltree Trilogy, set in Sydney and around Newcastle.

Maitland came to both crime fiction writing and the river city around the same time.

In December 1989, when the earthquake struck Newcastle, Maitland was living on The Hill. His friend and future wife, Margaret, was living nearby in Cooks Hill. The disaster that threatened to pull their homes apart pushed them closer. They moved in together because Margaret’s house was badly damaged, they married in 1990, and, in the search for a historic home, they shifted to Maitland. By then, Barry was writing a crime novel.

“I started writing at the time of the earthquake as a kind of reaction to the earthquake,” he reflects. “It was against all the chaos of what was going on, living inside that cordon [around the city centre].”

In his writing at least, Barry Maitland could exert control. All paintings, buildings and books, he says, are about their producers making “a small world, where they have control, to create something that is interesting, challenging, exciting, whatever it is”.

The earthquake was not the first time Barry Maitland experienced chaos about him. He entered a world tearing itself apart.

WHEN Barry Maitland was born in 1941, the Second World War was raging. His family lived in a city called Paisley, in Scotland. While they were far from the front line, the effects of war flowed up and down the nearby River Clyde, with its vast shipyards.

“I do remember the gas masks and the air raid warden from next door sharing the same shelter in the garden, sitting there with his tin hat on,” says Maitland.

At the end of the war, after Barry’s father, James, returned from service, the family moved to London to further his career as an architect. Barry recalls helping his Dad build models of his design projects, and “I remember as a little boy sitting on his knee, and he’d show me how to draw”.

But once his eyes were filled with art, particularly the work of Van Gogh and Jackson Pollock, Barry’s drawing became more abstract.

“It used to really annoy my father, who used to see me doing this stuff and would say, ‘Why don’t you try and draw a building?’,” Maitland says. “It was going to architecture school that knocked that out of me, or stopped me. Frustrated me.”

While he studied art at school, Barry listened to his teachers, who told him he wouldn’t make it with brushes. But, as his 2016 exhibition indicated, he has kept painting for pleasure, and to observe. As a young man, however, he concentrated on the meticulous drawing of design, studying architecture at Cambridge University. His future was set, following his father. Yet when Barry was 20, James Maitland died of cancer.

For the son, the loss was tragic. Yet, “in a way, it was liberating, because then I was going to have to make my own way.

“And I was fortunate that it was a time, during the 1960s, of a tremendous building boom in Britain,” he says.

Maitland was involved in the design of a new town near Liverpool and another in Scotland, before moving to the industrial city of Sheffield. He worked in an architects’ office within the university, helping students bridge the gap between training and the practice of architecture.

In the decade he worked in Sheffield, Maitland found himself doing increasingly more administrative work, rather than teaching and creating, and he grew restless. In 1983, he saw an ad in the Times’ higher education supplement for a head of the architecture school at the University of Newcastle.

“I knew one thing about Newcastle,” Maitland recalls. “I’d read a very interesting article about the school of medicine and its problem-based learning, which was so close to what we’d been trying to do at Sheffield.”

Maitland flew half way around the globe for a job interview. He was struck by the idea he could be moving from one steel town to another – only this one had irresistible surf. Newcastle enticed Barry Maitland to make the big move. In 1984, he took up the position at the university and enjoyed developing a problem-based learning model.

By the early 1990s, having settled into the job, his marriage to Margaret and his new home in Maitland, Barry was writing crime fiction. His first novel was published in 1994.

On his website, Maitland says, crime writing “felt like coming home”. It’s hard to imagine this gentle-looking and polite man feeling that way. At times, he detects people looking quizzically into his eyes, as if thinking, “What the hell’s going on in there?”

“Well, we all have secret imaginative lives,” Maitland shrugs. “I don’t go around planning real murders, I must say.

“For me, I don’t think crime writing is about crime. It’s about resolution, about putting people into awful situations and they triumphantly emerge from them - or not. What the crime element does is to make it compelling, where the stakes are so high.”

Novelists can shape their world on the page; life is not so easily plotted. Maitland was increasingly unhappy in his university job, as his time was being devoured by administrative tasks.

Then, in 1999, his 32-year-old son from his former marriage died.

“I was suffering from depression,” Maitland recalls. “Everything’s black, you drag yourself into work, kind of looking at the gloomy side all the time.”

Asked what effect that had on his writing, he frowns.

“If I looked at the books I wrote at that time, I don’t know if they would be blacker, I don’t know,” he replies. “I haven’t thought about it.”

By 2000, Maitland had decided to leave his university job, and to devote his time to writing. Gradually, with the help of Margaret, the blackness faded. The turmoil and twists were largely confined to his writing. Although that process can still torment him.

Certainly, writing I have ups and downs, I’m, ‘This is absolute rubbish. I can’t do it. I just can’t do it’,” he muses. “But if you just keep plugging away at it, if you don’t give up, just keep going back and writing a few more words ... the answer comes.”

The architect remains in the novelist: “Right from the first crime novel, the way I begin is … with a place.

“Imagine a place. Then imagine the people who live in that place and the kind of relationships they have.”

The best-laid plans hatched during research can unravel in the writing and the re-writing. But even so, Maitland has been producing a novel every 18 months or so. The stories are from his imagination, but Maitland has relied on the perspectives of others, including a police detective and a doctor friend, along with Margaret, to critique his work and offer advice. His wife is particularly critical of one area of his writing.

“The sex scenes usually,” he laughs. “I’m no good at them.”

“Have you got better at them?”

“No! I can’t do it. Hopeless. I get it excruciatingly wrong.”

Maitland is working on his next crime mystery book, he’s looking at other writing projects, and he intends to do more landscape painting. Even so, don’t suggest this makes Barry Maitland a Renaissance man. He’s just being human, searching for a solution to what we all ask ourselves: How do I express what I want to say?

“The trouble is that I haven’t solved the problem, and that’s what’s so frustrating,” he says. “How to do it, what works best. How can you get across what you see.”