EVEN before it has reached her lips, Julie McIntyre can find a deep sea of pleasure in a glass of wine.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

“Well, here’s the thing about wine that I think is really important,” she says, as she admires the pale straw beauty of Tyrrell’s famous Vat 1 semillon in her glass at Scratchley’s restaurant.

“Sitting and swirling and sniffing and allowing it to open out is as pleasurable to us as drinking it.”

I try not to choke on my mouthful of semillon, as I sputter, “Really?!”

“Yes!,” she replies. “Drinking it is also pleasurable. But this extends the pleasure.”

In wine, Julie McIntyre has found not just pleasure but a career.

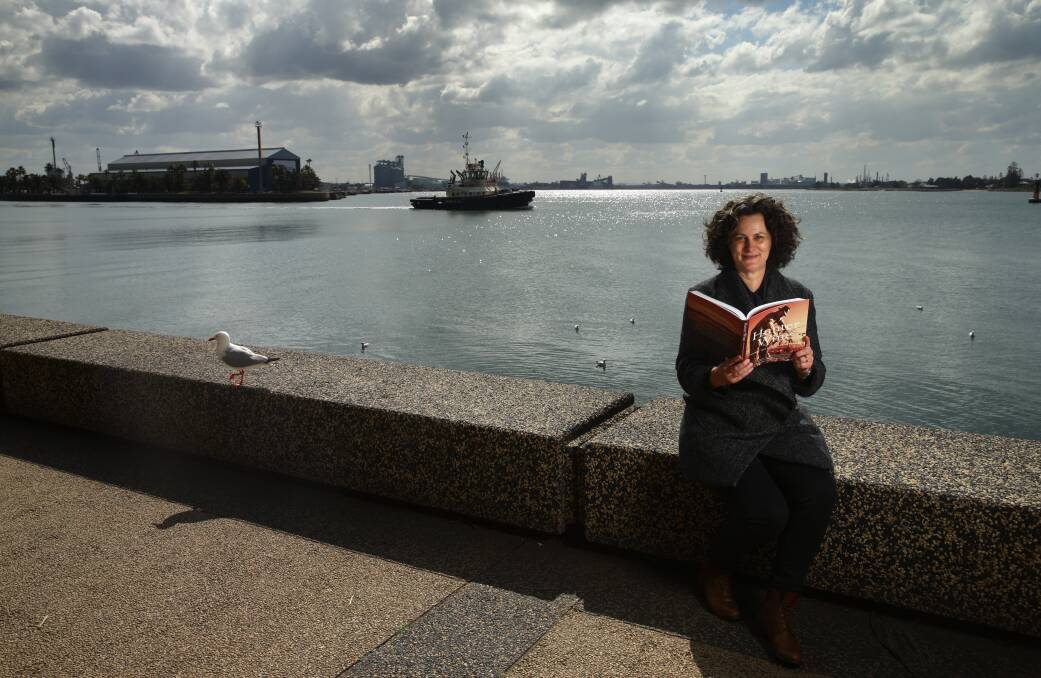

As an academic at the University of Newcastle, Dr McIntyre is one of Australia’s leading wine historians. She is the co-author of a new book, Hunter Wine, which examines the place, the people and industry since its origins in the valley in 1828.

Yet wine flows through more than just this region’s past, and the nation’s. It has carried Julie McIntyre back through her own family tree, and from those roots a vast area of research has blossomed for her.

JULIE Williams was born in 1967 - “an excellent year for wine in the Hunter Valley, as it happens” - and her early life was spent on the land.

Her parents had a cattle and sheep farm near Cassilis, and both sets of grandparents were farmers in the Mudgee and Gulgong areas. She recalls spending a lot of time travelling between the properties, particularly after her parents divorced, “not entirely unrelated to the difficulties of farming”, when she was eight. Growing up on farms had a profound effect on her.

“The foundation of my imagination as a writer and as a historian was certainly laid through that experience,” she muses. “And my sense of living in a landscape that was very different on each of the farms.

“The farm my parents had was kind of right on top of the Great Dividing Range, really dry, lots of the trees on the property were ringbarked, and there was a kind of an ethereal ghostliness to those areas that were ringbarked.”

Her maternal grandparents’ farm was just outside Mudgee on the Cudgegong River flats, and “it always struck me the colours and the smells were different”.

Her grandparents, Alfred and Laura Kurtz, had a vineyard, producing Mudgee Wines. The Kurtzes tilled tradition on their land. Alf Kurtz’s great grandparents, Andreas and Rosina, had planted the first vines in the 1850s. Andreas Kurtz’s memory is preserved not just in old vines but in a poem written by Henry Lawson, who was born in the district.

And the family winery is imprinted in the memory of Alf and Laura Kurtz’s grand daughter: “It was a corrugated iron shed, it had concrete vats with waxed interiors. I could close my eyes and see the whole thing.

“What I do vividly remember, as wine was fermenting, is the smell of the winery. There’s a power to it, in the way there’s a power to smelling wine in the glass or smelling vinegar, something like that.”

“The magic for me was definitely in being in the winery. And I associate the really beautiful smell of fermenting wine, or wine that’s under storage – or we would help put labels on, the wine being corked and capsuled and bottled – I associate that with my family.”

As a child, Julie followed her mother over the range to Murrurundi then to the coast, near Taree. There, as an 18-year-old just out of high school, she met her future husband, Phillip McIntyre. He was a musician. These days, he is an academic and author, and, like his wife, works at the university.

“He was just lovely company, and that’s still the case for us,” McIntyre says. “He has a really fascinating way of thinking.

“He’s very gentle. Really I’d never met anyone like him who seemed as well-read… He has an attachment to slapstick comedy that baffles me.”

In the late 1980s, the couple moved to Newcastle, and Julie became a journalist, first in radio, then television.

“I really loved it,” she recalls. “I loved the storytelling side of what we did. I loved the daily access to the way the world is changing.

“One moment I might be writing about a problem with a road black spot and the next thing going out to do a doorstop with the Prime Minister. That’s the joy of regional news.”

McIntyre took a break from journalism, when she had the first of her two sons, Isaac (who now works as a journalist for The Newcastle Star), in 1994. Her son’s arrival marked a huge change in life and career, as she moved on from journalism.

“At that time you couldn’t job-share in journalism,” she says. “That is absolutely the reason I didn’t go back to a newsroom.

“So I stepped away from journalism, which was really hard to do. This very sweet little six-month-old exerted a far more magnetic pull at that time.”

Julie McIntyre enrolled at the University of Newcastle. She studied history: “What mainly intrigued me was how we research and write. These were the sort of things I was interested in as I was studying.

“There was no particular agenda to start with, but I could see this was a pathway I could take.”

The pathway to her future was crafted from the past. For her honours degree, she studied her grandparents’ agricultural books, and how their contribution to a reviving Australian wine industry in the 1960s was recorded and interpreted.

“It was an unusual choice for me to work on something that was family history, but it wasn’t family history in the sense I wasn’t doing genealogy; I was looking at my family’s profession, as it were,” McIntyre says.

“Through that process, I discovered that there was very little attention to wine in Australian history. It was a fortunate series of events that led me to that particular type of study.”

So began McIntyre’s academic adventures in wine history. She completed a doctorate, with her thesis wearing the elegant title, A "Civilised" Drink and a "Civilising" Industry: Wine growing and cultural imagining in colonial New South Wales. In 2012, she released an acclaimed book, First Vintage: Wine in Colonial New South Wales.

“Academia is like farming. I often say it’s seasonal, it’s incessant, it’s very rewarding,” she says. “It’s not the sort of job where you put your tools down after a certain amount of time and go home.”

Now McIntyre and her sociologist colleague John Germov have delved into the historically rich local soil, with the writing of Hunter Wine. McIntyre has also curated an exhibition about the Hunter’s wine industry at Newcastle Museum.

The Hunter Wine book looks at characters through six generations, including the great families who have shaped the region; names such as Tulloch, McGuigan and Tyrrell.

But the book points out that a wine region is about more than individuals, and that a raft of forces – environmental, economic, and social – have had a huge impact on what ends up in the bottle, and on the industry and the Hunter through the years.

“My and John’s hope is that this will change the way you understand the Hunter wine region, by reminding us it’s an agricultural history that’s connected to broader forces,” McIntyre explains.

“John and I hope this book and this exhibition are evidence of something very valuable, not just to this region but to the nation.

“The Hunter wine region is Australia’s oldest continually producing wine region. Wine is really important, it’s not just a commodity, but a part of Australian lives and global lives.”

While considering the industry’s history in the valley, and its resilience, McIntyre says she reflected on what would happen if the Hunter as a wine region was lost.

As we talk and eat Spanish mackerel and tuna, a couple of coal ships have slid past us into port, preparing to consume and carry away hundreds of thousands of tonnes of the Hunter. Those huge ships are a reminder of the growing competition for the Hunter’s land among all who rely on it.

“The Hunter wine region has an assured future, if it’s possible to protect existing vineyard land from the encroachment of rezoning for mining,” McIntyre says.

“What would make a big difference in the Hunter Valley is to have state heritage listing for the most important sites that contain vines that are of genuine historic value, which is to say they’re old and still producing.

“I think it would make a difference if people who would like to see the Hunter Valley remain as a wine region spoke out. I think wine consumers need to talk about whether they’re concerned that coal mines would encroach into areas where it would change the look of the landscape.

“The look of the landscape matters a lot in the Hunter Valley because it is a tourism region. So if you can see a coal mine from a really beautiful vineyard location, that really changes it.”

Finishing our semillon, I ask Julie McIntyre if she is popular at dinner parties, because of her connection to wine, or does that scare people from inviting her?

“Strange to say, no one seems to mind if I tell stories. Which is lovely!,” she replies. “I’ve somehow managed to not become what some people pejoratively refer to as a ‘wine bore’.

“The wine itself is not the point of what I do; it’s the people. Even though the people and place are the critical things for me, the wine in the glass is a product of that. And that’s how I understand that wine. Not in terms of wine education or judging, or something like that.”

Peering into the final drops of her wine, Julie McIntyre concludes, “For me, there’s a whole glass full of stories in there.

“A whole world of stories in there.”