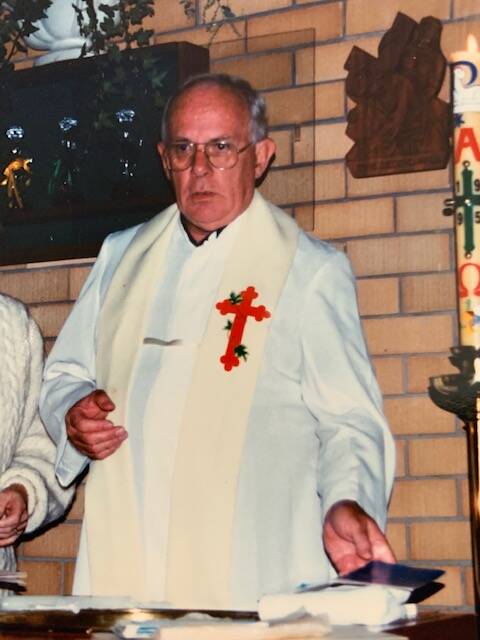

Soon after, Audrey had arranged to speak with Hart again and she began talking to him about Andrew. "I think he got a bit fed up," Audrey told the courtroom, "and he said something like, 'Look, it's been going on forever. The Romans had their little boys, the Greeks had their little boys, the English aristocrats had their little boys.''' I said, "So that makes it alright, does it?' "I have not spoken to him since."

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

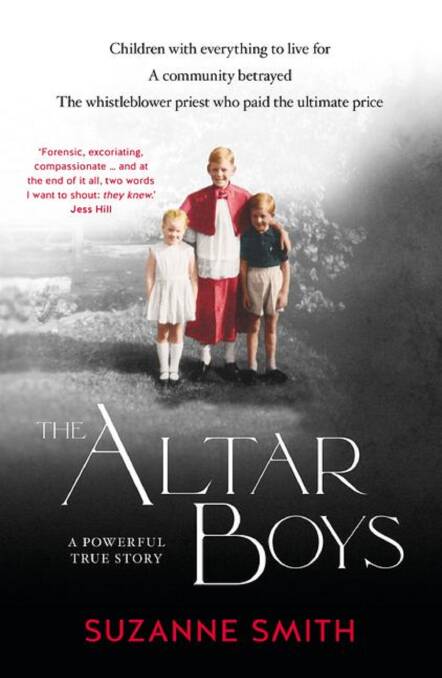

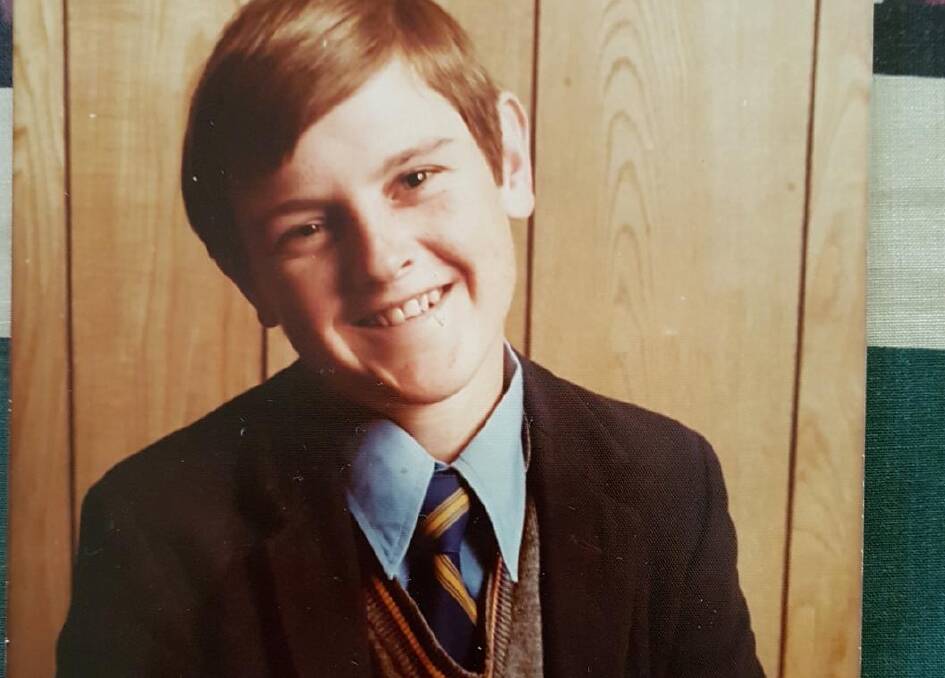

This paragraph - in which Newcastle's Audrey Nash, whose abused son Andrew killed himself at 13, speaks of senior cleric Monsignor Allan Hart - comes some 250 pages into The Altar Boys, Suzanne Smith's disturbing history of the horror decades of clerical paedophilia in the Catholic Church in our part of the world.

It's a true statement, and anyone who doubts it has not read their history. It was such a celebrated part of ancient Greek culture that it's all over their pottery, as a look at any major museum collection will tell you.

But that doesn't make it right. Far from it. However the gilded youth of Greece and Rome coped with the attentions, there's a welter of evidence to show that generations of stuttering Englishmen suffered from the sexual and physical violence in their disciplinarian schooling system. And that system was here, as well. Smith sets the scene at what was Marist Brothers Hamilton - now St Francis Xavier's College - in more genteel surroundings now than they were then.

"The school's disciplinarian Irish culture had been imported many decades before, and in the early part of the 20th century it wasn't unusual to witness violence between students and teachers. Brothers would fight bare fisted with students in order to settle scores and to show who was the superior being, and students would frequently be caned for minor rule-breaking such as uniform breaches. Often parents wouldn't object because they thought these strict boundaries were good for the boys - after all, they'd been brought up the same way. Their deep respect for the Church caused them to never question the authority of the Brothers. Their sons, dressed in second-hand blazers, inherited that respect and were full of fear and awe for the Brothers."

There are many stories in Smith's book, which weaves them in and out in more or less chronological order. Many on the church side of things were either repeat offenders or those enabling repeat offending by moving them from parish to parish, school to school. A lot of the names are unfortunately familiar to many Newcastle Herald readers. But a lot of the detail is not.

The book is dedicated to the late Steven Alward, a journalist and former head of international news and Radio National at the ABC, who began his career as a cadet at the Herald. He had asked Smith to investigate the death of a friend, Father Glen Walsh, who took his own life in November 2017.

From the book: "A day after Glen's death was announced in the media, I'd received a Facebook message from Steven:

Hi Suzie. Not sure if you heard but a priest who was due to give evidence against the Archbishop of Adelaide about a paedophile priest in Newcastle [James Fletcher] killed himself on Monday. His name was Father Glen Walsh and he was a very close friend of mine when I was in primary school. He lived in my street. He tried to report Fletcher but he was treated appallingly by the Church in Newcastle (mainly Alan [sic] Hart) ... The collateral damage of this hideous story goes on and on. Hope all is well with you. Love s.

Steven was referring to Monsignor Allan Hart, his and Glen's assistant parish priest way back when they were kids, as someone who had bullied Glen.

I replied, 'Yes, I know. It's terrible ... How are you? Can we meet for a coffee?'

Life got away from us. I went overseas in December 2017, then Christmas came and went. As I was preparing to contact Steven in January 2018 about our catch-up, the terrible news came through.

Steven had died before he could give me any more information. But I had made a pact with him, and I felt the need to keep my promise. And so here is what could be described as his very last commission as an editor."

The Altar Boys follows Walsh on a journey that starts in hope and ends in tragedy. We pick up the story at Chapter 16: "The old guard rules with an iron fist. - Father Glen Walsh"

"On 27 April 2004, Detective Sergeant Peter Fox was sitting at his desk at the Maitland Police Station when Father Glen Walsh came to see him.

Fox's experiences with the clergy over the past year had made him wary of them. But after Glen sat down and they talked for some time, Fox realised this priest was different. Glen told the detective he was praying for a just outcome to the case. He said he was fearful of the consequences of his decision to go to the police, although he knew he had no other choice. He added that Bishop [Michael] Malone didn't know he was at the police station.

Fox called Brendan [Byrne, who was alleging abuse by Fletcher] the next day and the young man came into the Maitland Police Station to make his statement on 11 May 2004.

Over the next few months, Fox would sometimes have a cup of tea with the priest, in his office at the police station. They would talk philosophically about institutional sexual abuse. How it worked on the inside, and why the hierarchy wasn't proactive in dealing with the clerical sexual abuse issue. How he and many other clergy wanted to see the Church change. How they wanted to see a new generation taking control.

Glen told the detective, 'The old guard rules with an iron fist. They don't want things to change and it's going to continue on in the same tragic way unless something monumental happens.'

Glen asked Fox a rhetorical question: 'Do you know what it is like for a priest to give mass after your predecessor has been arrested for paedophilia?'

For months, Glen's relationship with the diocese had suffered because of his response to the Fletcher matter. Fletcher's supporters in the parish weren't happy with him."

Later that year, Smith writes that Father Walsh was living out of his car in Sydney, before finding a teaching job in Sydney.

"Glen had thought a lot about what survivors of clerical sexual abuse really needed from their Church, and he wanted to communicate this insight to his bishop. So, on 10 September 2004, five months after Glen had left active ministry and the diocese, he wrote to Malone. He let the bishop know that he'd found a teaching position in Prestons and would not be returning to the diocese as a priest. 'Therefore,' he said, 'I write to you for two reasons: 1. Why I have left. 2. I need your help.'

On the first point, Glen did not hold back:

Priesthood is a calling I take very seriously, but have never felt accepted in your diocese, my home.

The struggle to identify myself in the presbyterate was made more difficult by three of my appointments and their intrinsic connections to paedophilia and sexual misconduct.

Every victim I have counselled, simply seeks an apology. The lies, denials and the distance by the Church simply compounds the abuse ... As our Bishop, you are the Sacrament who is Christ; therefore, dare to go in persona Christi to the victims and their families in your diocese, not with lawyers in tow and legal rhetoric, but with the Love of God ...

- Priest Glen Walsh in his letter to Bishop Malone in 2004

In 1995, before I was ordained a Deacon, I informed you of my one and a half years of abuse at the hand of Brother Coman Sykes fms [Fratres Maristae a Scholis], hoping you would keep this information in mind when appointing me to parishes.

Appointing me to Taree (after Father Vincent Ryan), Gateshead/Redhead and Windale ... and finally at Branxton/Greta and Lochinvar (after Father James Fletcher) while knowing I am a victim of abuse at the hands of [Sykes] meant that I was daily confronted with my own pain, as well as having to minister to those parishioners effected [sic] by abuse claims made towards their clergy.

While obviously not intended, the message I received through these appointments was that the 'abusive' Church is alive and well, unsympathetic and unapologetic.

I suggest it is always unwise to place a newly ordained priest in parishes where clerical sexual abuse, alleged or proven, has traumatised the community, especially if he is a victim of Church sexual abuse.

This, surely is a job for the most senior and experienced priest not the recently ordained.

Michael, I write about this not because I am angry or want to accuse, but I believe you need to know you were right in your last letter when you stated your wonder at my 'mysterious restlessness from time to time.' I never really settled into priesthood even though I know the priesthood is my true vocation, my life. I remained 'unsettled' for the reasons above mentioned. And I presumed, knowing my story, you would understand and accommodate.

My restlessness has never been about the priesthood or the demanding ministry within, but finds its genesis, within the abusive human nature, found to my amazement in so many people, especially clergy.

One of the tragedies regarding all this scandalous clerical abuse, is that the Church is rapidly losing its credibility and its purpose. That it is taking civil law to expose these priest predators and provide justice to the victims is unnecessary and continues to cast a bleak shadow over a life-giving faith.

As Bishop, you have the power to drag this diocese out of the shadow. Every victim I have counselled, simply seeks an apology. The lies, denials and the distance by the Church simply compounds the abuse ...

As our Bishop, you are the Sacrament who is Christ; therefore, dare to go in persona Christi to the victims and their families in your diocese, not with lawyers in tow and legal rhetoric, but with the Love of God and the prophetic faith of Jesus Christ.

Making them wait for the court to rule is wrong. You can show us what is right by spending time with them, praying for and with them, calling them to the heart of the faith, wherein peace and healing resides ...

Glen went on to make a request for funds, asking, 'Would you consider helping me Bishop?' and explaining his financial situation.

This, surely is a job for the most senior and experienced priest not the recently ordained.

Michael, I write about this not because I am angry or want to accuse, but I believe you need to know you were right in your last letter when you stated your wonder at my 'mysterious restlessness from time to time.' I never really settled into priesthood even though I know the priesthood is my true vocation, my life. I remained 'unsettled' for the reasons above mentioned. And I presumed, knowing my story, you would understand and accommodate. My restlessness has never been about the priesthood or the demanding ministry within, but finds its genesis, within the abusive human nature, found to my amazement in so many people, especially clergy.

One of the tragedies regarding all this scandalous clerical abuse, is that the Church is rapidly losing its credibility and its purpose. That it is taking civil law to expose these priest predators and provide justice to the victims is unnecessary and continues to cast a bleak shadow over a life-giving faith.

As Bishop, you have the power to drag this diocese out of the shadow. Every victim I have counselled, simply seeks an apology. The lies, denials and the distance by the Church simply compounds the abuse . . .

As our Bishop, you are the Sacrament who is Christ; therefore, dare to go in persona Christi to the victims and their families in your diocese, not with lawyers in tow and legal rhetoric, but with the Love of God and the prophetic faith of Jesus Christ. Making them wait for the court to rule is wrong. You can show us what is right by spending time with them, praying for and with them, calling them to the heart of the faith, wherein peace and healing resides ...' Glen went on to make a request for funds, asking, 'Would you consider helping me Bishop?' and explaining his financial situation. 'I hope you accept my letter in the spirit in which it is written,' Glen concluded. 'I do need to acknowledge why I have left the priesthood I love so much and to seek your help to re-establish myself in a safe and fulfilling environment. I am happy teaching and thank God I have this profession to turn to.'

Several weeks later, on 29 September 2004, Malone replied.

He attached a cheque for $20,000 and began by explaining that it was 'to assist with costs for getting established in Sydney'. But he went on to say:

I am disappointed in your comments about 'the abusive Church is alive and well, unsympathetic and unapologetic.' I reject what you have written and can only put it down to the fact that you are not travelling well. You have no understanding of all the work I have done with victims of sexual abuse. To dismiss my pastoral ministry with these people, tense negotiating sessions, aggravation and grey hairs with a few scathing remarks is very hurtful.

I do not expect you to know the truth of these matters but I would hope for an acknowledgement that there might be more involved than you do understand.'."

From 2008 to 2017, Father Glen Walsh and Steven Alward watched closely as Detective Sergeant Kristi Faber went on to convict a large number of priests and brothers with hundreds of charges relating to close to 180 victims.

The Maitland-Newcastle Diocese was now all over the television, radio and online media, and the two old friends read all the information they could about each offender and where he had operated.

Similar teams of police were also looking at the Anglican Church in Newcastle. Sometimes Faber would have six matters running at once in the courts. Some investigations ran for more than eleven years. And she still believed her team had only scraped the surface in the diocese."

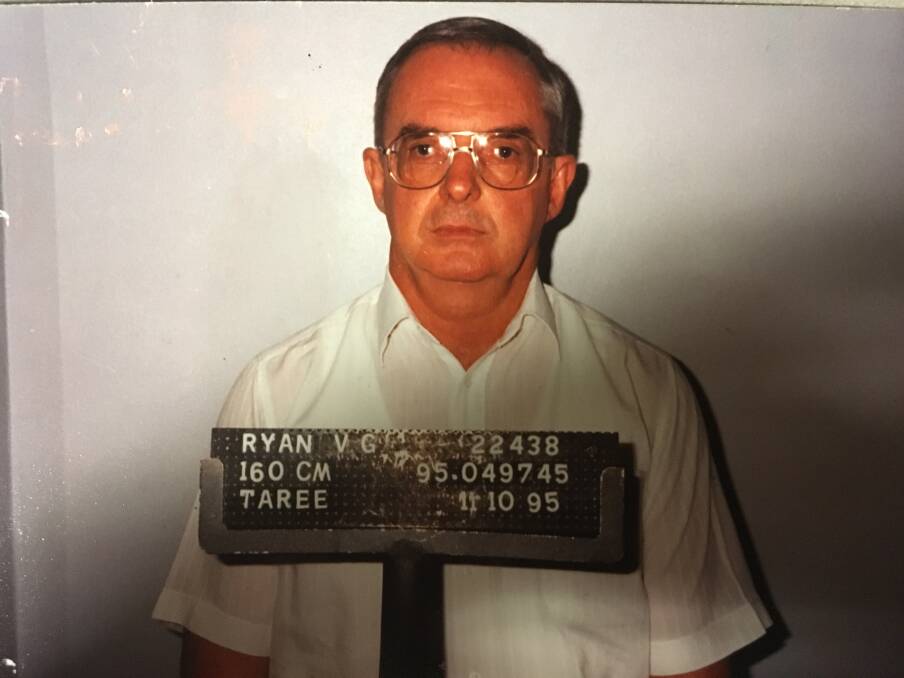

Although The Altar Boys rightly credits Joanne McCarthy for the bulk of the reporting up here, one of the first blows was struck in 1995, when the now notorious Father Vince Ryan was arrested.

"On 16 October 1995, the Newcastle Herald broke the story: an unnamed priest in the diocese had been arrested on child sexual assault charges. Father Vince Ryan's actual arrest took place five days before at Our Lady of the Rosary Parish in Taree, on the outskirts of the diocese. He had been moved there in 1995 to avoid too much scrutiny, but this strategy had failed - his offences were too many and too horrific.

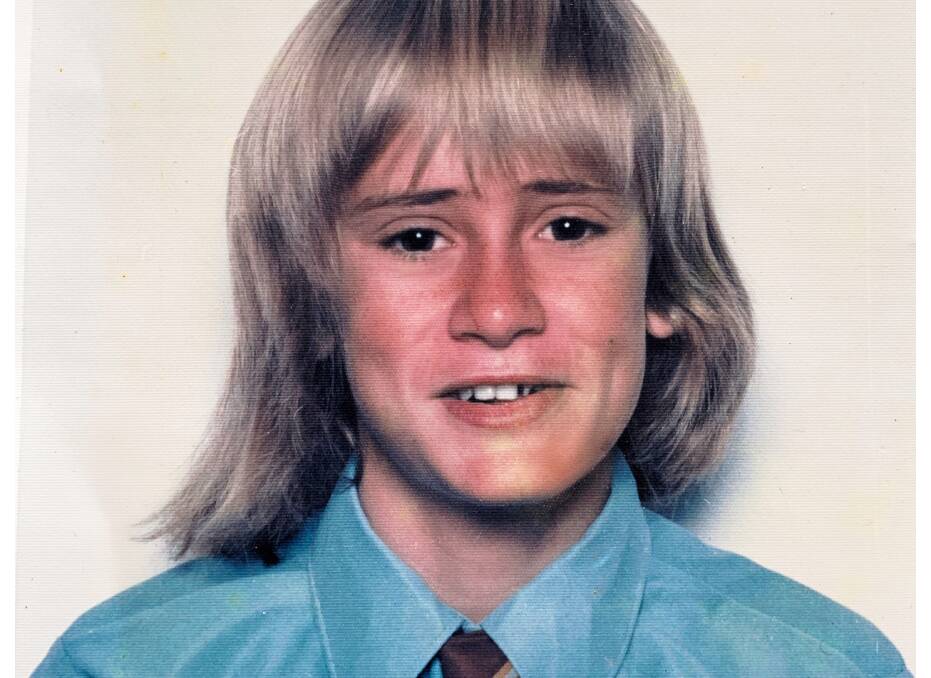

Senior constable Troy Grant had been sitting at his desk in the Newcastle Police Station when an intake officer told him that a young man wanted to see him. In 1992, at the age of 16, this young man had been in a terrible car accident while driving Father Ryan's car. He'd spent four months recovering in hospital.

There was also a list of altar boys, all victims, with a cross drawn next to each of their names. It was like a trophy of Ryan's conquests.

- Suzanne Smith describing part of a 'bounty' of evidence against Father Vince Ryan

What he told Grant, on that spring day in October 1995, would be seared into the constable's memory for the rest of his life. Ryan had abused this boy between the ages of 12 and 16, committing more than 200 acts of sexual assault on him. The abuse had occurred from 1989 to 1994 when Ryan was the parish priest in Cessnock, a rural town about an hour west of Newcastle. The assaults only stopped when the boy was in hospital.

Grant issued simultaneous warrants on Ryan's home and several Church properties, raiding the secret archives and gathering hundreds of documents on the case. Ryan's home yielded a bounty of material including his diary.

Another great score was his registration papers, which helped to verify the statement of a victim who said Ryan had assaulted him in the back seat of his car, a brown Kingswood. There was also a list of altar boys, all victims, with a cross drawn next to each of their names. It was like a trophy of Ryan's conquests. Grant knew the scrappy bit of white paper was one of the best things an investigator could find: corroborating evidence.

Nothing could have prepared Grant for his long investigation into the first paedophile priest to be charged in the Maitland-Newcastle Diocese. Victims would come forward from all of Ryan's parishes, including Hamilton, Cessnock and Merewether."

As Father Glen Walsh had said in one of his letters to Michael Malone, the Bishop had appointed him to various parishes to replace offending priests, including Taree after Ryan, and Branxton after James Fletcher.

"This Depression-era street in Newcastle was like many others. Rows of Federation-style dark-brick bungalows, pre-war architecture with mature lemon trees in the front yards, kids' toys strewn across the freshly mown grass, and cars in various states of repair.

But there was something striking that couldn't be avoided from any vantage point: at the beginning of the street, a large white cross marked the boundary of the Marist Brothers Hamilton School. In one of those houses, a priest was preparing for his death.

The night air was cool on Monday, 6 November 2017. Darkness was enveloping his home. The only light was from an aromatic candle, wafting a scent through the dimly lit rooms.

In the dancing shadows, illuminated by the flickering candlelight, stood the priest's private altar. Among the statues of Jesus and several sets of coloured rosary beads was a prayer card.

This priest was Glen."

- Excerpts from THE ALTAR BOYS by Suzanne Smith, ABC Books.

- 1800 551 800 Kids Helpline

- 13 1114 Lifeline