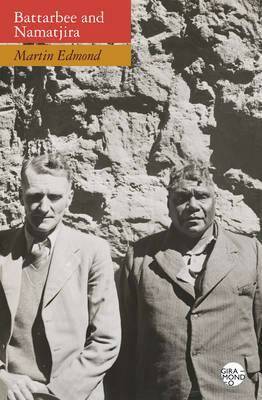

Battarbee and Namatjira, by Martin Edmond,

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Published by Giramondo, $29.95

ALBERT Namatjira is a household name but it takes a real interest in Australian art history to identify Rex Battarbee for his place in the 20th century's artistic narrative.

Edmond tells that story: the friendship and creative exchange between the two men who met at Hermannsburg in Western Arrernte country in 1934 and remained close until Namatjira's death in 1959.

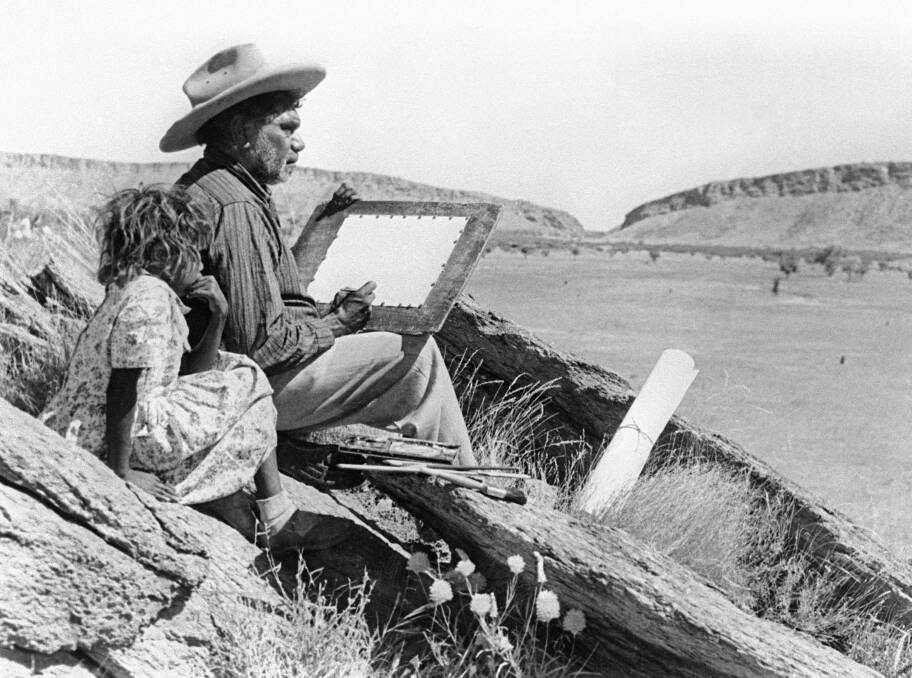

Namatjira, already producing poker-worked artefacts for the tourist trade, saw the potential of watercolour painting as a means of making a living by 'painting Country' 40 years before the Western Desert (dot painting) movement began at Papunya. Battarbee was a catalyst in Namatjira's development, exchanging painting techniques and art materials for first-hand experience of Arrernte country. Both shared Christianity as a guiding principal, but Namatjira had two faiths.

Namatjira has been the subject of several books, from the tragic Namatjira: wanderer between two worlds (Joyce Batty, 1963) to the scholarly The Heritage of Namatjira (Hardy, Megaw and Megaw 1992) and the most comprehensive (but not the first) retrospective catalogue, Seeing the Centre: The art of Albert Namatjira (Alison French, 2002). However, until Edmond's book, the rich and enduring friendship between Battarbee and Namatjira has been largely ignored. That this friendship also featured in the recent Big hART/Scott Rankin theatre production, Namatjira, now in development as a documentary, suggests an eagerness for such nuanced stories of cross-cultural and relational agency: how well does Edmond deliver?

The book begins with an introduction to Arrernte alcheringa (or 'Dreaming') and pre-contact ways of life. The Lutherans and the anthropologists are similarly announced, followed by separate biographical chapters on Namatjira and Battarbee.

These chapters border on the pedestrian, as if Edmond is struggling with editorial demons and losing out to excess detail.

He does, however, map out divergent world-views, social politics and the cult of historic personalities within - and beyond - the Hermannsburg mission with its mostly German and Arrernte population.

The author circles in slowly before introducing the main protagonists to each other well into the book, and the second half is where the action begins.

Edmond draws on several sources (omitting footnotes), relying especially on Battarbee's diaries: here personal accounts of painting and life in Central Australia slowly build a gentle character portrait.

Elsewhere, largely extraneous characters and events weigh down Edmond's narrative.

One realm of contention which Battarbee's diaries fail to settle is whether Namatjira intentionally anthropomorphises the landscape. Any visit to ancestral country with Aboriginal people - let alone artists - should dispel any doubt that each rock, tree and waterhole is animated by ancestral presence, often figuratively envisaged.

Battarbee and Namatjira covers a period of shameful Australian history, and Edmond does elucidate on the early developments of the contemporary Aboriginal art market with all its ethical and logistical challenges and he pays careful attention of events leading to Namatjira's arrest and his premature death.