Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

WHEN the Pasminco lead smelter at Boolaroo closed in 2003 it left behind more than a century’s worth of toxic pollution.

The surrounding community and environment continues to suffer from the plant’s legacy.

Despite official assurances the area was safe following a state-sanctioned abatement program, a joint Newcastle Herald and Macquarie University investigation has found alarming levels of lead and other heavy metals remain in homes and public places today.

The findings raise serious public health questions for present and future generations.

A STATE-sanctioned clean-up of toxic land in north Lake Macquarie has failed, with new tests revealing alarming levels of lead, arsenic and other poisons in homes, playgrounds and parks.

A Newcastle Herald investigation has found dangerous levels of heavy metal pollution across three suburbs, a catalogue of government failings and residents feared sick from past exposure.

The results come just two years after the completion of a project – approved by the NSW government – designed to protect residents from 100 years of pollution produced by the former Pasminco lead and zinc smelter at Cockle Creek.

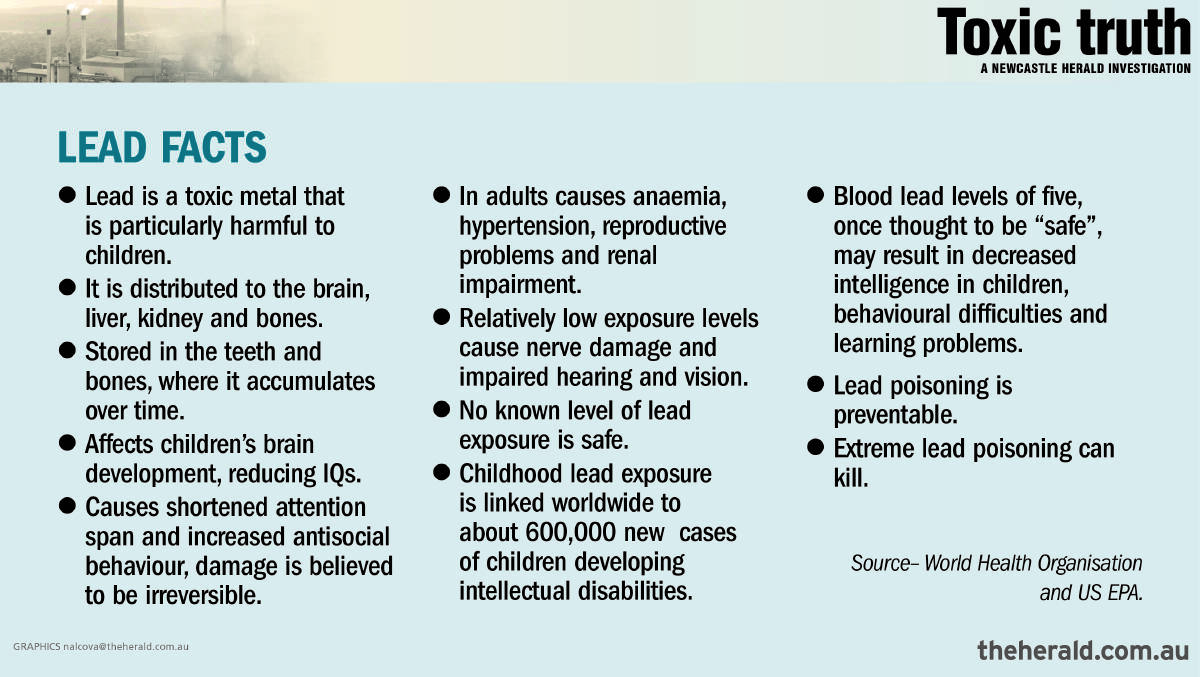

Lead experts said exposure to the contaminated soil and dust could cause sickness, brain damage, behavioural problems and retardation in children.

More than 130 soil and household dust samples were taken from homes, sports fields, parks and schools in Boolaroo, Speers Point, Argenton and Teralba as part of the joint Herald and Macquarie University investigation.

Results, analysed at the National Measurement Institute, found lead in soil more than 14 times the Australian residential standard of 300 parts per million (ppm) and arsenic inside a home almost 300 per cent above the safe level.

A sample taken at Tredinnick Oval, Speers Point, believed to be a smelting waste product known as black slag, contained 17,500 ppm lead, or almost 30 times the recommended level for recreational areas.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Do you know more? Want to share your story? Email dpage@fairfaxmedia.com.au

----------------------------------------------------------------

Two soil samples from Boolaroo Public School’s playground exceeded the Australian standard by 300 per cent and a sample taken outside Speers Point Public was eight times over the limit.

There were several cases where testing carried out by the Herald revealed significantly higher levels of lead at homes compared to the government-sanctioned testing done two years ago. This was despite the fact that the program was designed to ‘‘reduce lead levels in surface soils around homes’’.

Environmentalists, politicians, academics and community members have seized on the results as proof the NSW Environment Protection Authority has failed its job of policing an effective outcome for residents.

Macquarie University environmental scientist Mark Patrick Taylor said the failure to clean up the towns had left a “legacy of environmental contamination” that would continue to “debilitate the community’’.

He described the program, known as the Lead Abatement Strategy, as ‘‘wholly inadequate’’.

The controversial “cap and cover” strategy was secretly approved by the EPA in 2008, did not address dust inside homes and excluded commercial and public land.

‘‘Lead has a half-life of at least 700 years, which means generations to come will continue to ‘enjoy’ the failures of the clean up,’’ Professor Taylor said. “When we look at the houses what we can see is that there is no statistical difference between properties that have been abated and those that were not.”

The EPA has been aware of chronic contamination in suburbs surrounding the former smelter that closed in 2003 for decades, but appears powerless to enforce a thorough clean-up.

Hundreds of tonnes of dangerous heavy metals were emitted by the smelter, one of the region’s chief polluters, over 106 years.

The EPA and Pasminco administrator Ferrier Hodgson defended the abatement strategy, describing it as ‘‘effective’’.

EPA director of hazardous incidents and environmental health, Craig Lamberton, said it was the ‘‘most comprehensive program of its type in Australia’’.

He conceded the EPA had done no testing to evaluate its effectiveness.

‘‘The objective of the [Lead Abatement Strategy] was to reduce human exposure to elevated levels in lead in residential properties by creating a barrier to any residential lead,’’ he said. ‘‘It was not about removing the lead completely.’’

Sydney University geoscientist Gavin Birch described the readings after the abatement project as “extraordinarily high’’.

Under increasing environmental and financial pressure, Pasminco went into voluntary administration in 2001, with debts of $2.6billion, and the smelter closed two years later putting 360 workers out of jobs.

Administrator Ferrier Hodgson has spent years remediating the 200-hectare industrial site which is now on sale, amid plans for a $750million redevelopment, known as Bunderra Estate which means “amongst the hills” in the local Aboriginal language.

It is planned to include 500 to 800 dwellings, new businesses, sporting fields and open space.

Planning documents show residential land on the Pasminco site had to be remediated to the Australian standard of 300 ppm for lead in soil.

But for residential properties surrounding the smelter, the EPA ignored the Australian recommended guidelines and accepted a lesser standard.

Boolaroo Action Group spokesman Jim Sullivan said it was simply the latest chapter in a long history of how the regulator had failed the affected communities.

He said the EPA had also refused to take action on the millions of tonnes of black slag distributed throughout the region over years. Residents have never been told the locations of the highly toxic material.

Mr Sullivan’s group wants money from the sale of the Pasminco site to be set aside for a future fund for further remediation works.

‘‘Pasminco’s land has been cleaned up, at least we think so, and they’ve given us a second-rate job,’’ he said.

A home in First Street, Boolaroo – declared ineligible under the abatement-strategy terms because it was once owned by Pasminco – recorded lead in soil of 4230 ppm, or 14 times what was acceptable just metres away.

International lead expert Professor Bruce Lanphear, of Simon Fraser University in Canada, said leaving properties so badly contaminated was ‘‘ridiculous’’.

Professor Lanphear said the approach ignored volumes of scientific research detailing the link between blood lead levels and soil.

He said the latest test results meant further work was required to remove contaminants.

“It is a major public health problem for these communities,” he said.

“Any lead in soil will contribute to a child’s blood lead concentrations.”

But head of the Hunter Public Health Unit Dr Craig Dalton said previously high blood levels in north Lake Macquarie children were caused by emissions that stopped when the plant closed.

There has been no blood testing carried out since 2006.

After being alerted by the Herald about the results, the health unit responded by announcing it would start blood testing children under five next year.

Despite being dogged for decades over pollution in the area, the government surrendered a 1995 legal requirement for Pasminco to remediate homes. This would have forced the plant to fix houses in Boolaroo, Argenton and Speers Point with soil lead levels above 600 ppm.

Instead, the government negotiated directly with Ferrier Hodgson, which argued the condition lapsed when the smelter closed, and accepted the abatement strategy to deal with the pollution – not a full remediation program as demanded by the community.

Boolaroo business owner Stan Kiaos described the move as “unbelievable” and said residents had been left with an inferior job that had failed.

Ferrier Hodgson has repeatedly declined to reveal how much was spent on its residential abatement strategy. It was carried out at 1226 homes, with 63 per cent receiving an educational DVD on how to limit lead exposure. The remaining homes had top soil spread on lawns, grass replaced and a handful had contaminated soil removed.

Officially, Lake Macquarie City Council went along with the plan. Internally, there has been great cause for concern.

Documents obtained by the Herald under freedom of information laws reveal repeated attempts to raise concern about the effectiveness of the strategy.

“In the absence of an adequate justification, council staff are unable to fully support an approach whereby contamination remains on-site (in most cases) with relatively minor levels of topsoil or grass cover,” the council wrote to the then NSW Department of Climate Change and Water in October 2007.

Council’s concern was given further cause four years later when it received advice from the Office of Environment and Heritage, against council policy, that up to 1000 ppm lead in soil was “acceptable” within the abatement area, but not outside.

Professor Taylor described the discrepancy as “environmental injustice”. “They will effectively use a poor abatement program in order to bolster money that will go back to the creditors,’’ he said.

The Newcastle Herald and Macquarie University collected more than 130 soil and vacuum cleaner dust samples from homes and public spaces at Boolaroo, Argenton, Booragul, Teralba and Speers Point.

Samples were analysed at the National Measurement Institute for antimony, arsenic, cadmium, lead and zinc.

Half the public sites had unsafe levels of lead.

All but one residential site contained elevated lead levels.

The highest residential soil reading was 14 times the recommended safe level for lead and a sports field was 30 times over the safe limit.

There was no significant difference in contamination levels between properties that participated in a government-sanctioned project designed to clean up the areas and those that didn’t.