After so many years of peering into polluted water, John Sutton figured he was looking at just another submerged plastic bag.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

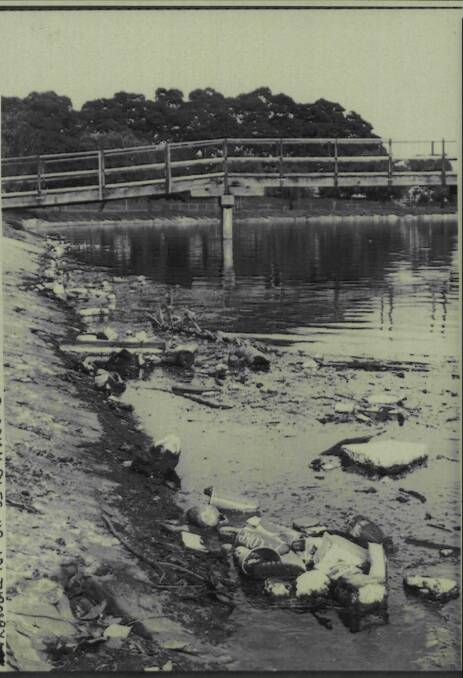

Since moving to Tighes Hill in the early 1980s, Sutton had seen a lot of plastic bags in Throsby Creek, along with just about every other thing that people discard and throw away. Bicycles, shopping trolleys, toys, used syringes; they all ended up in the creek.

In the process, it seemed, people had discarded respect and love for the creek. In the eyes and minds of many Novocastrians, Sutton recalls, the creek was nothing more than “a dirty, stinking stormwater drain”. That is, if they thought about it at all.

As a long-time member of the local residents’ group and Throsby Landcare, Sutton had been trying to convince a city to realise what it had flowing through its heart.

He had wanted Newcastle to see this as a creek once more. But he had always known it was going to be a long battle, pushing against the long tide of history of the creek being abused and ignored.

So there was a sense of sad familiarity when he looked into the water on that day in 2012. But then Sutton realised what he could see was not a plastic bag but a couple of stingrays cruising just below the surface.

“That was a pretty amazing moment,” Sutton asserts, “to realise that life was getting up the creek.”

More than course through the life of Newcastle, Throsby Creek helped a tiny convict settlement grow into an industrial city.

Those first white arrivals gave the creek a name. Surgeon Charles Throsby had been appointed to Newcastle, after it was founded in 1804. In turn, the creek gave Newcastle something to build on. Its waters fed into the harbour that cradled ships from the colony’s earliest days, along its banks were industries, from an abattoir to a brewery, and the low lying areas near the creek were cultivated.

Yet the more Newcastle was developed, the more Throsby Creek suffered. The creek’s catchment is vast, as a web of watercourses reach deep into suburbs as distant as Kotara and Lambton. When land was cleared for farms and houses in those suburbs, silt sluiced down the watercourses into Throsby Creek. Industries used the creek as a waste discharge channel. Yet the creek remained a playground, with people fishing and swimming in its waters, and a sailing regatta was held on it.

But the attitude the creek was now primarily a working waterway literally hardened in the early 1930s, when the banks were concreted. The creek was shaped into, and treated as, a stormwater drain. Many of the watercourses feeding into the creek were also concreted. So there was a drainage system comprising dozens of branches pouring urban run-off, and the contaminants and rubbish it contained, into Throsby Creek.

The creek became off-limits for fishing because of the pollution, and, by the time John Sutton moved into the area, many viewed it as “a liability to be near”.

Sutton was among a swelling group of locals from Tighes Hill, Maryville and Islington, who campaigned for authorities to do something about the creek. By 1989, the group had made ground with the state government. A Total Catchment Management strategy was produced for the creek.

“It was the first strategy to bring all the stakeholders together, and it was about looking at it not just from the stormwater aspect, but the ecosystem, the community, all those issues as well,” Sutton recalls.

That strategy flowed into action, on the water and along the banks, including mangroves being planted, and a cycleway was built. The residents also kept up their campaign to restore the creek, using “hearts and minds” programs to engage the community.

A play about the creek was produced, a beer called Murk Draught was brewed (“it was actually pretty good”, reckons Sutton), and the regatta was revived. Only the competitors ran with their boats along the banks, to highlight the poor water quality.

“In a way, it was as a mockery that we were beside the water, but we couldn’t get into it,” says Sutton.

Yet improvements continued, another major strategy was done in 2001, and gradually life was drawn back to the creek. Indeed, Throsby Creek has been given a new lease of life, as it has become a desirable place to live, work and play by, and on.

As John Sutton says, people “started to think of it as a creek again”.

To better understand how much the creek has changed, and how much attitudes towards it have shifted as well, I figure I should get my feet wet. But just my feet.

I decide to kayak Throsby Creek from where it meets Styx Creek opposite Tighes Hill TAFE down to where it flows into the main harbour. Statistically, it’s not far, less than three kilometres. But this journey isn’t about the length covered; rather, it’s about gauging the depth to which Newcastle has reconnected with the creek.

The options for launching a kayak, or engaging directly with the water in any way, near the the creeks’ junction are scant. Up here, the concrete walls give the impression this is still primarily a drain. I use some old stone steps and get my feet not just wet but muddy in a bed of silt.

Once I’m paddling, the creek swirls to life just ahead of the kayak. The surface is fretted and ruffled by fish dashing out of the way. When I lift my blade out of the water and sit still, a school of mullet glides languidly past just below. It’s a wonderful sight.

I paddle beyond the wedge of concrete that marks the creeks’ confluence and head up Styx Creek, slicing between the TAFE campus on the right and the graffiti-daubed walls of old factories on the other.

Styx Creek is a curious name. In Greek mythology, the Styx is the river dividing the land of the living from the domain of the dead. Approaching a concrete sediment trap across Styx Creek a couple of hundred metres from the junction, I feel as though I’ve reached the boundary between a living waterway and one that looks dead. On the other side, corralled by a floating boom, is a carpet of rubbish, carried down the drains and destined for Throsby Creek and the harbour, if it wasn’t caught here. According to a 2004 report, about 20 cubic metres in sediment and about 10 cubic metres in floating rubbish are trapped here each month.

“You don’t want to go beyond there,” cautions a bloke sitting outside a former factory downstream from the concrete barrier. “That side is a no-go area.”

The bloke’s name is Paul and he is strumming a guitar, while watching the tide sluggishly come upstream.

“The water coming up this way is mostly natural,” he explains before pointing to the barrier, and beyond. “The garbage comes from up there, where human civilisation is.”

Paul says he spends a lot of time by the Styx.

“I’ve had some beautiful meditative moments here,” he murmurs. At night, when the TAFE lights are bleeding across the surface, Paul says, “it’s almost like a Venetian canal”.

Paddling downstream, past the confluence of the creeks, I notice the banks are thriving with people - and dogs - playing. Joggers, cyclists and parents pushing prams share the space.

The banks are also thriving with vegetation; the severe concrete surfaces give way to rock walls and mangroves.

“When we first moved to Tighes Hill, there was not a single mangrove here,” John Sutton had said, as he surveyed the creek’s ragged green flanks while standing on the footbridge linking his suburb to Islington.

Sediment has also accumulated in the creek. This section was dredged a couple of decades ago, but Sutton believes it needs to be cleaned out again: “It’s not as bad as it was, and may it never get to that again, but the build-up of sediment is there.”

Hunter Water, which is responsible for the channel in this part of the creek, is undertaking a study into the need for dredging. The report is due mid-year.

“Dredging is a big and expensive operation,” says Darren Cleary, Hunter Water’s chief investment officer. He explains the operation could cost between $4 million $9 million, depending on how the material is disposed of - and what contaminants, such as heavy metals, it contains.

“So we’re doing some testing to see what’s in the material.”

Darren Cleary says the study is looking at whether the sediment build-up affects the channel’s ability to deal with heavy flows and prevent flooding, but it is also considering any environmental impact.

“We have to ensure whatever we do doesn’t damage the mangroves that are starting to re-establish,” he says.

Just beyond the curtain of mangroves downstream of the footbridge are streets filled with reimagined, and increasingly expensive, real estate on both sides of the creek.

A generation ago, Tighes Hill, on the left bank, and Maryville, to the right, were working class suburbs located too close to an unloved stormwater drain. Now those little workers’ cottages and bungalows are highly desired, in part because of their proximity to the creek.

New developments are also popping up. The former Hunter Research Foundation site in Maryville is to become a “bicycle-oriented” housing development known as Velocity. A number of its townhouses are selling for more than a million dollars.

“Seriously, that would have been unheard of five years ago, and you would have been committed 10 years ago, if you said that was going to happen,” says real estate agent Andrew Walker, from Street Property Group.

For prices to go up, just add water, and Mr Walker, who has been selling real estate in the area for 34 years, believes the properties near Throsby Creek will only continue to increase in value.

“It’s a more than viable alternative to getting something on Newcastle harbour itself,” he says.

Barbara and Leigh Wardle are among the recent arrivals in Tighes Hill.

They moved in 2016 from Melbourne into a home literally a stone’s throw from the creek. And with them, they brought a fresh perspective, free of remembering how the creek used to be.

“I get very distracted, just gazing at the water,” says Barbara, as we sit on their back veranda, watching a couple drift by in a tinny. “It changes four times a day, because it’s tidal.”

“I find it very therapeutic,” adds her husband. “We don’t paddle and fish in it, but I get enjoyment from watching the birdlife; egrets, waders, pelicans.”

“I don’t think of it as a creek, I think it’s a billabong. It’s too wide to be a creek.”

“It should be a river!,” declares Barbara.

THE stretch between Graham Bridge linking Maryville and Tighes Hill and the Hannell Street road bridge about 700 metres downstream holds stronger reminders of the creek’s industrial past.

Warehouses and light industrial sheds squat above cracking pieces of the old concrete banks and drainage pipes dribbling into the creek.

The ugliness of the creek’s edges in places is not lost on Hunter Water.

Darren Cleary says the organisation has begun looking at the advantages and costs of “naturalising” more of Throsby Creek’s banks. Cleary says while the concrete walls were once an engineering solution, he sees “a lot of value in getting them ripped up; one of them being people’s engagement with [the creek], seeing it as a natural watercourse not a stormwater channel”.

Beyond the Hannell Street Bridge, the creek curves to the south. Winding through the mangroves on the outside bend is a boardwalk. If offers respite from inner-city living, but not from mosquitoes.

Marooned among the vegetation is rubbish carried in and left behind as the tide drops.

Occasionally larger items, such as shopping trolleys and bikes, are plucked from the creek, indicating that a few still view this as little more than a dump.

Near the mangroves, a fisherman named Roy is hoping to draw something more palatable from the water. The NSW Department of Primary Industries rules no shellfish or crustaceans are to be taken from the creek upstream from the Cowper Street Bridge, which is about a kilometre downstream from here. Roy has three crab traps out.

“I like my seafood,” Roy says. “You can eat out of here, but people are scared to.”

His only concern standing in the water up to his waist are bull sharks. Roy says he’s seen three in his time fishing along the creek and has even hooked one.

People’s fear of sharks in the creek are fed by history. A 12-year-old boy was killed by a shark further downstream in 1920, and a 15-year-old died after having his leg bitten off in 1936. The Coroner warned after the 1936 fatality that boys took “terrible risks” bathing in places such as Throsby Creek.

More than 80 years on, the creek is an aquatic pleasure ground once more.

Along the Carrington shore is a beach and the headquarters of Newcastle Rowing Club.

Long before the sun has climbed above the grain terminal in Carrington, groups of rowers carry sleek racing shells out of the shed and down to the water.

For an hour or so, they will train on the creek, cutting fine incisions into the surface, following in the long-faded wake of all those who have rowed these waters since the club was formed in 1870.

Watching the rowers train is club president John McLeod. He has been rowing on the creek since 1993 and recalls having to duck under the old Cowper Street Bridge. Back then, the club was based further down the harbour. Its headquarters have been on the Carrington shore since 2009.

“We’re very lucky to get this site on Throsby Creek,” he says. The club, which has about 100 members, holds a regatta out the front, laying out a 400-metre, three-lane sprint course, and rowers train here every day.

“It’s magnificent,” McLeod says. “Once you’re down here, you think, ‘Where else would you want to be?’.”

The rowers hardly have this stretch to themselves. There are the members of the Newcastle Hunter Dragon Boat Club, the Newy Paddlers, the Newcastle Stand Up Paddle Club, the Newcastle Outrigger Canoe Club, and a stack of individual paddlers and rowers. What’s more, there is a public boat ramp nearby.

“One thing to watch out for is over-population, because it [the creek] is not that big,” says John McLeod.

A spokeswoman for NSW Roads and Maritime Services, which is responsible for the creek up to the Hannell Street Bridge, says compliance with boating rules is considered good, with only a few complaints.

“Operators of passive craft share the water equally and respectively, often using the beach rather than the boat ramp to launch their craft,” the spokeswoman says.

Perhaps the most active passive-craft group off Carrington are those practising yoga on paddle boards.

While the morning rowers heave past, the yoga devotees defy gravity and belief on the boards. Occasionally, one loses balance and splashes into the water.

“It’s fantastic here,” says one of the instructors, Dylan Henry, from ECS Boards Australia. “The only downside is the water is dirty. The water quality is getting better. But the sand also isn’t clean.”

His voice is not alone. Amy Williams watches her two dogs splash in the shallows out the front of the rowing club.

The Maryville resident says she loves the dynamic character of Throsby Creek, “but the [water] quality not so much”, with floating rubbish and the occasional odour. Yet that’s not about to disrupt her morning routine, or her life by the creek.

“There’s always something happening here, it’s a great place,” she says.

Hunter Water’s Darren Cleary is direct in his reply, when I ask him if he would swim in Throsby Creek.

“No. Because of the nature of the run-off that goes into that waterway, it means there are times when it wouldn’t be suitable for swimming.”

“I think secondary recreation [in other words, those on boards and in vessels] is okay.

“But actually getting in, certainly after rain, no, you shouldn’t be. And that’s clear, that’s what the advice is, you’ve got to be careful after rainfall. Because we do have storm water running in, which will have contaminants in it.

“After heavy rain, unfortunately, our sewer system can overflow as well.”

The armada of water users off Carrington provides a procession of entertainment for the hundreds of residents in the apartments and townhouses of the Linwood precinct along the opposite bank.

Built on the site once occupied by wool stores, the housing development was one of the earlier markers of an area and creek being regenerated.

In the midst of the village is The Source Cafe, attracting residents and passers-by from the cycling and walking track out front, and even a few paddlers off the water.

“It’s getting more and more popular,” waitress Pru Docherty says of both the creek and the cafe, as one encourages the popularity of the other.

Docherty is aware the creek bank location entices diners and provides a sideshow for them, and for the wait staff. She admits to finding it “funny to watch the SUP (stand up paddle boarding) lessons”.

Downstream from the Cowper Street Bridge, the creek feels as though it narrows, as its banks become more congested. Leisure businesses and the maritime industry sit cheek by jowl.

There’s the Commercial Fishermen’s Co-operative, with its fleet of net-festooned trawlers. The co-op looks across the creek to the Maritime and water police launches.

Further along from the co-op on the Wickham shore are cafes and the winter forest of masts outside the Newcastle Cruising Yacht Club, which has 180 berths in the creek.

The club’s CEO, Paul O’Rourke, says for the marina, it is a big advantage to be in the lower reaches of the creek, so close to an all-weather port. Yet what washes down through the stormwater drains can become a challenge, as floating plastic and expensive boats’ engines don’t mix well.

“We’ve certainly got a vested interest in keeping the creek clean,” O’Rourke says. His staff regularly scoop rubbish out with nets, and so do sailors whose boats are berthed at the marina.

Squatting between the club and the co-op is Midcoast Boatyard and Marine. The boatyard maintains and repairs vessels at its berths in the creek, and on the land. Walking through the yard, amid the hulls of yachts and cruisers suspended in cradles, is the owner Joe de Kock.

He feels deeply connected to Throsby Creek. His business relies on it, he and his family live by it at Maryville, his wife paddles on it, and he runs along its edges each morning.

“I’m not trying to pretend it’s Sydney Harbour, but for a little city like this, there’s a lot of people living around it, and a lot of people using it,” he says of the creek.

Joe de Kock says when Throsby Creek comes up in conversation, “most people tell you how bad it used to be”. De Kock can remember what it used to be like outside his yard when he moved here in 2003. There was no walking and cycling path; “you’d walk through dust”.

“There was nothing happening here,” he recalls. Now there’s so much happening, to the extent that when he is taking a boat out into the channel, he checks both ways for other water users.

But de Kock thinks there is potential for this section of the creek to develop further as a marine precinct.

He was keen to secure some of the old dockyard land and facilities on the other side of the creek, where the floating dock Muloobinba squatted for almost 35 years, before she was towed away in 2012.

De Kock wanted to expand his business and meet growing demand from Sydney boat owners. However, French company and defence contractor Thales and the NSW government announced last year they were developing that area into a major ship repair and maintenance facility.

De Kock believes Newcastle is allowing an opportunity – and money – to sail by to other ports: “For Throsby Creek, it will be nice to see naval ships, but it would have been good to have had the biggest and best boats from Sydney Harbour here.”

Joe de Kock reckons his yard adds to the character of Throsby Creek.

“I think people like to see a working harbour,” he muses. “They like the restaurants and yachts, but they also like the industry.”

PADDLING around the bend where ships once berthed at Throsby and Lee wharves, I’m about to leave the creek and enter the Hunter River, and the main part of the harbour. Not that there’s any line to cross. The water flows on, like time itself.

As for the future of Throsby Creek, a new strategy is being drafted. It is to be considered by the Throsby Creek Government Agencies Committee, which includes representatives from local and state government authorities, business and two community delegates, John Sutton and the rowing club’s John McLeod.

The committee’s chairman, State Member for Newcastle Tim Crakanthorp, says the “2018-2024” report will look at continuing improvements to the creek and catchment over the next six years and, as the title indicates, will be released this year.

“I see it [the creek] as continuing and improving as a recreational facility,” Crakanthorp says.

Hunter Water’s Darren Cleary recounts how on a recent visit to Germany, he joined many others in swimming along a creek flowing through Munich. He is confident that one day, he will be able to do the same in Throsby Creek.

“It will be in my latter years,” he adds. “It’s a longer term project, it’s not going to happen quickly, but it is achievable.

“It’s a wonderful asset, and it could be an even better asset, as we continue to work to improve the amenity along the creek, and the quality in the creek.

“It requires us to work with all the partners in the community to achieve that goal.”

But let’s take stock. As we paddle or row on it, walk along it, or dine beside it, we should gaze into the water and reflect on just how far Throsby Creek has come in a generation, and what its revival means to Newcastle’s life, now and into the future.

“It’s a source of pride for the whole community,” John Sutton concludes.

“It’s great we can revive this creek. The fact you can turn something like this from a dirty drain into an environmental and recreational asset is a fair achievement, I think.”