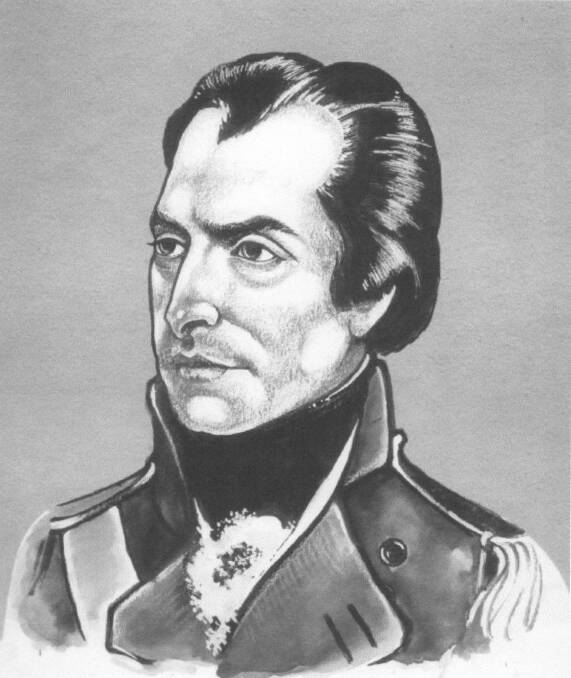

WILLIAM Paterson preferred being a botanist, but became a soldier by necessity.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

He’s especially remembered in this region as the first European to survey ‘Hunter’s River’ and others, charting Coal Harbour (now Newcastle) plus upstream from present-day Maitland often in miserable conditions in mid-1801. Here, Paterson was in his element – exploring fresh territory and collecting flora and fauna – pursuing his passion for natural science for about five weeks.

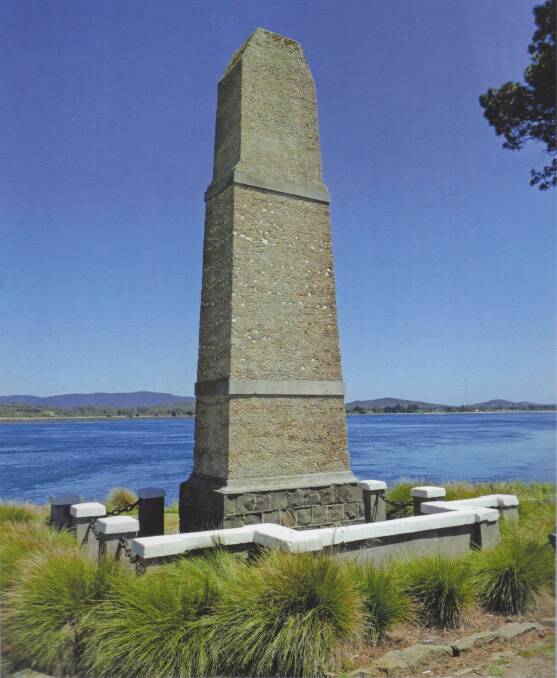

Paterson River and the valley township of Paterson (from 1833) are named in his honour. And also, oddly enough at first glance, is Paterson Island, in Launceston, in the former Van Diemens Land, now Tasmania.

Paterson established a southern settlement there to thwart French ambitions (among other reasons) in 1804, and it so pleased early NSW governor Philip Gidley King that he called it Patersonia. But William Paterson rather wisely changed it (in 1806) to ‘Launceston’ in honour of King’s birthplace in Cornwall, England.

Today though, history probably remembers Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson best as the rebel governor of NSW who governed illegally throughout 1809. That’s after his officers deposed the legitimate governor William Bligh, of earlier Bounty mutiny fame, in a military coup. In his defence, the easy-going Paterson had played no part in the coup but, on returning urgently to Sydney, he found himself in a dilemma.

He could either reinstate the indignant, tantrum-prone William Bligh, or govern the colony himself until he received advice from England. Paterson chose not to reinstate Bligh and instead backed his officers. But he suffered from the stress of it before dying two years later.

During the drama, the ill Paterson left most duties, both military and civic, to Lt Col Joseph Foveaux, who became, in effect, the real rebel governor.

The military junta ended when Lachlan Macquarie sailed in with his troops in two ships and became the new NSW governor on January 1, 1810.

Only a few months later, in May 1810, William and Elizabeth Paterson sailed for England. En route they passed New Zealand on whose southern extremity today can be found ‘Foveaux Strait’ and ‘Paterson Inlet’, so named by sealing captains “in gratitude to the two rebel governors for lifting the ban on sealing”.

Paterson did not complete his voyage. He became very ill and died at sea near Cape Horn on June 21, 1810. The next day his body was committed to the deep with a 13-gun salute.

And that might be normally the end of the tale. For who now champions Paterson’s reputation and legacy with his name forever sullied by his regiment, nicknamed ‘the Rum Corps’, after it deposed the NSW governor William Bligh?

An insightful biography has long been overdue, and now Dr Brian Walsh has come to the party with a book aimed at rescuing both William and Elizabeth Paterson “from historical obscurity”.

In the new work, titled William and Elizabeth Paterson – the Edge of Empire, Walsh has done an outstanding job of analysing primary sources to chronicle the life and times of the power couple.

Walsh deftly outlines Paterson’s overlooked achievements while assessing him as a friendly, outgoing man, much loved in private life, despite his weakness as an administrator and his lack of political skill.

Paterson, it seems, was “bewildered by the intrigues and manoeuvres of others”, “too easily led” and “often too good natured to make tough decisions”, according to Walsh.

The author also challenges popular views of the ‘Rum Rebellion’ saying the NSW Corps has been judged unfairly based on the simplistic legend of a decadent ‘Rum Corps’ and exaggerating the adverse consequences of the trade in liquor by officers.

Worse still, Walsh writes, it “masks the achievements of officers who transformed the colony from a miserable settlement to an economy with emergent private enterprise”.

Maybe all true, but this reader is uneasy with the fact it was an armed uprising to the commercial benefit of military men which could easily have cost Bligh his life.

Nevertheless, on the new governor’s arrival in Sydney in 1810, Lachlan Macquarie was met with pleasant surprises. He imagined “that after two years of rebel government that the colony had become a pirate state like the famous one at Madagascar, a feral settlement outside the control of legitimate authority”. The reality was quite the opposite. The colony was in a sound state with new infrastructure, including large warehouses on the wharves of Sydney and Parramatta, being built.

Author Walsh also rejects what he says is the enduring myth of the NSW ‘Rum Corps’ being formed from the dregs of society, being full of thugs and villains. Instead, he paints them as simply a cross-section of working-class 18th century society, complete with rough characters.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Paterson refused to live in her husband’s shadow. Walsh documents that she and a friend established he Sydney Female Orphan School, becoming the first women in Australia to manage a public institution.

She impressed in a male-dominated society, navigating all the political storms that surrounded her husband only to be widowed at age 40. Elizabeth had once arrived in the colony feeling lonely, isolated and homesick. Years later, in 1810, she didn’t want to return to England. Australia had become her home, her special place, Walsh writes.

What more is there to tell of William Paterson, the placid botanist who explored the Hunter River and settled northern Tasmania? Plenty, including that in his lifetime he was recognised by Britain’s peak body for the advancement of science and that today more than 20 plant species are named in his honour.

Earlier in his career, between 1777 and 1779, Paterson made four journeys into the interior of southern Africa, covering 9000 kilometres in two years and also named the Orange River.

In his lifetime, Paterson also introduced the giraffe, koala and thylacine (Tassie Tiger) to British science. Add to that his role as an early Blue Mountains explorer (in 1793) naming the Grose River and being the first European to travel up it and also to arrange importing the first merino sheep into Australia. Along the way, Paterson challenged the wily wool pioneer John Macarthur to a duel and almost died after being shot.

Of interest, with Sydney’s second international airport to be built at Badgery’s Creek, is that Paterson once employed free immigrant James Badgery to tend his plants on the voyage to Australia from Britain in 1799.

This is a book to devour slowly, to fully appreciate the depth of diligent research; a book to treasure.

The sale proceeds from the this first-class production of 220 pages in full colour will go to the Paterson Historical Society. After its launch on Sunday (May 20), at Woodville Hall, the book will be available from Paterson Court House and McDonalds Bookstore, Maitland, for $45.